-

1. Introduction

Corporal punishment of children remains a significant and controversial issue in the Czech Republic. In the winter of 2021, the Minister of Labour and Social Affairs, Marian Jurečka, stated that corporal punishment can help parents ‘define boundaries’,1x Radek Dragoun & Barbora Doubravová, ‘Slapping a child can set boundaries, I don’t want to forbid it to parents, says Jurečka’, 27.1.2022. which indicates that corporal punishment is still widely accepted in society. In a recent survey, conducted in 2023, 58% of parents admitted to having corporally punished their child at least once, and 35.7% believe it is an integral part of upbringing.2x Charles University, 1st Faculty of Medicine, ‘Physical punishment is demonstrably harmful to children. How much do Czechs use them?’, 27.6.2023. Widespread support for corporal punishment is declining only very slowly, with 63% of parents surveyed in 2018 reporting that they had used corporal punishment in parenting at least once. Open Men’s League, Physical punishments, 2018. These statistics highlight the widespread acceptance of corporal punishment among Czech parents.

Estimates indicate that 14% of children in the Czech Republic, or roughly 280,000 children, are at risk of family violence.3x Klára Španělová, ‘Abused Children Interrogated by 47 People. Domestic violence often goes unreported, experts say’, Aktuálně.cz. Annually, around 9,000 cases of child abuse, exploitation, and neglect are reported to the Authority for Social and Legal Protection of Children. However, the number is estimated to be up to ten times higher. This estimation is supported by ACE research, which states that only about 10% of child abuse cases are detected and reported.4x Miloš Velemínský and others, ‘Prevalence of Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) in the Czech Republic’ (2020) 102 Child Abuse & Neglect 104249. The non-profit organization SOFA compared the number of identified cases by the Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs (MPSV) and estimated that in 2022, 367,000 children, or 17% of all children, were at risk of physical abuse.5x The SOFA authors based their findings on research data from ibid. ACE stands for Adverse Childhood Experience, www.societyforall.cz/prestanme-prehlizet-ohrozeni-deti. Therefore, qualified estimates suggest that between 280,000 and 367,000 children are at risk in the Czech Republic. Given that more than one-third of parents consider corporal punishment an integral part of upbringing, the number of children at risk of being hit and punished in other ways is likely significantly higher.

Due to considerable social support towards corporal punishment of children, the country has not yet passed a law banning such treatment of children. Despite numerous calls from international bodies such as the United Nations and the European Committee of Social Rights, the Czech Republic has yet to adopt explicit legislation banning all forms of corporal punishment in family settings. This article explores the current legal framework governing corporal punishment in the Czech Republic, analyses the enforcement of these laws at the level of individual municipalities, and discusses the newly proposed legislation to abolish corporal punishment entirely.

The article introduces the historical context and legislative background, and then describes the current legislation protecting children from violence and corporal punishment. That section explores the claims made by Czech authorities that children are fully protected from corporal punishment by law, analysing whether existing legislation explicitly prohibits corporal punishment in all settings, including the family environment. The next section of the article will present the legislation proposed in 2023. The description of the legislation will be followed by the quantitative research conducted on data from 2017 to the first half of 2024. The research compiles data on how individual municipalities enforce the legal norms described. This research examines whether Czech children are effectively protected from corporal punishment in their homes, as asserted by Czech authorities, on the data retrieved from the municipal authorities.

The aim of this article is thus to examine the level of protection of children from corporal punishment in their homes in written law and its application. This research uses a mixed-methods approach, combining qualitative and quantitative data collection and analysis. Legal texts, such as the Civil Code,6x Civil Code, Law No. 89/2012 Coll. Criminal Code,7x Criminal Code, Law No. 40/2009 Coll. and administrative legal acts will be analysed to evaluate the extent to which they prohibit corporal punishment in all settings. Reports from international bodies like the United Nations and the European Committee of Social Rights will provide an external perspective on Czech legislation. The main research question to be answered in this article can be formulated as follows: Are Czech children protected from corporal punishment in their homes, and does the current legal framework and its enforcement align with the Czech Republic’s claims that corporal punishment is already prohibited in all settings? -

2. Historical Context and Legislative Background

The UN Committee on the Rights of the Child defines corporal punishment as any punishment in which physical force is used and intended to cause some degree of pain or discomfort, however light.8x UN CRC, General comment no. 8: The Right of the Child to Protection from Corporal Punishment and Other Cruel or Degrading Forms of Punishment 2006, CRC/C/GC/8., para. 11. This includes actions ranging from spanking to more severe forms of physical punishment. The Czech Republic has been repeatedly urged by UN bodies and the European Committee of Social Rights to legislate against corporal punishment of children. Despite repeated recommendations, significant gaps in Czech legislation still need to be filled.

In 1997, the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child first urged the Czech Republic to adopt legislation prohibiting corporal punishment of children.9x CRC Concluding observations on Czech Republic, 1997, CRC/C/15/Add.81, para. 18 and 35. This concern was reiterated in 2003, highlighting the lack of legal regulations prohibiting corporal punishment in family settings, schools, and public institutions, including alternative family care. The UN Committee on the Rights of the Child recommended comprehensive legislative and administrative measures, including public education initiatives, to ban corporal punishment in all settings and ensure compliance.10x CRC Concluding observations on Czech Republic, 2003, CRC/C/15/Add.201, para. 40 and 41.

In response, the Czech government’s 2008 report suggested that the former Family Act11x Family Act, Law No. 94/1963 Coll. The law was repealed as of January 1, 2014. implicitly prohibited disciplinary measures that degrade a child’s dignity or endanger their well-being. The Act on Social and Legal Protection of Children further criminalises such measures with fines of up to 50,000 CZK, which equals € 2,000.12x The Act on Social and Legal Protection of Children, Law No. 359/1999 Coll., section 59(1)(h) of the Act The government stated that corporal punishment in schools and other institutions had been abolished since 1870 and noted that laws did not explicitly use terms like ‘punishment.’13x The Third and Fourth Periodic Report on Fulfilment of the Obligations arising from The Convention on the Rights of the Child. 2008. https://vlada.gov.cz/assets/ppov/rlp/dokumenty/zpravy-plneni-mezin-umluv/The_Third_and_Fourth_Periodic_Report.pdf, para. 133-135. A legislative proposal to ban corporal punishment in families was considered in 2010 but was never submitted.

In 2011, the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child reiterated its concern. It urged the Czech Republic to address the societal tolerance of corporal punishment through awareness campaigns and educational programs promoting alternative disciplinary measures. Although the ‘National Strategy for the Prevention of Violence against Children (2008-2018)’ was appreciated, it did not adequately address the elimination of corporal punishment beyond a planned ‘STOP Violence Against Children’ campaign.14x CRC, Concluding observations, 2011, CRC/C/CZE/CO/3-4, para. 39-42.

By 2021, the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child, along with other UN bodies such as the Committee against Torture and the Human Rights Council, emphasised the need for explicit prohibition of corporal punishment in all forms and settings, advocating for positive, non-violent, and participatory child-rearing practices.15x UN CRC, Concluding observations on Czechia, CRC/C/CZE/CO/5-6, 2021, para. 24. UN Human Rights Council, 2012, A/HRC/22/3, para. 94.88-94.90. UN CAT, Concluding observations, 2012, CAT/C/CZE/CO/4-5, para. 22. Despite these calls, the Czech Republic remains one of the few countries in the European Union that has not banned corporal punishment in family settings, often arguing that existing laws already address the issue.European Committee of Social Rights: Approach v. Czech Republic

The international pressure on the Czech Republic to reform its laws continued with significant developments involving the European Committee of Social Rights. In February 2013, the Association for the Protection of All Children (APPROACH) filed a complaint with the European Committee of Social Rights (ECSR). The complaint alleged that the Czech Republic violated Article 17 of the European Social Charter (ESC) by not banning explicitly corporal punishment in all childcare settings including families. Article 17 of the ESC ensures the right of children to grow up in an environment that fosters their development and protects them against negligence, violence, and exploitation. The Czech Government argued that the general prohibition of corporal punishment could be inferred from a specific provision of the 1964 Civil Code, which stated that a person has the right to the protection of their personality, their life and health, honour and human dignity, as well as their privacy, name, and personal expressions.16x Statement of the Government of the Czech Republic on the collective complaint filed against the Czech Republic for violation of the European Social Charter due to the absence of legislation explicitly prohibiting corporal punishment of children in the family, at school and other institutions and places, www.mpsv.cz/documents/20142/1037493/vi_2014_27_p1.pdf/9b9f3a82-d44d-314a-a9c3-634b5fae0b97. I would argue that the provision did not protect people from violence inflicted by other people, nor protected children from corporal punishment at home.

The ECSR had previously criticised the Czech Republic in 2005, 2011, and 2015 for non-compliance with Article 17 of the ESC, which mandates an explicit ban on corporal punishment in homes, schools, and other settings. The ECSR consistently interprets Article 17 of the ESC to include the protection of children from corporal punishment, stating that ensuring adequate protection is one of the ECS’s main objectives.

In its decision on the APPROACH complaint, the ECSR found that none of the referenced legal provisions explicitly and comprehensively banned all forms of corporal punishment of children. The ECSR concluded that even the Civil Code could be interpreted to allow corporal punishment for disciplinary reasons, because it permits it for educational reasons contrary to the ESC. In January 2015, the ECSR unanimously found that the Czech Republic’s practice violated Article 17 of the ESC. Following this decision, the Czech Republic is required to regularly inform the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe about the measures taken to address this issue.17x Decision on the merits: Association for the Protection of all Children (APPROACH) Ltd v. Czech Republic, Complaint No. 96/2013. -

3. Current Legal Framework

Czech Charter of Fundamental Rights and Freedoms

Although explicit prohibition of corporal punishment is lacking, several legal provisions offer indirect protection for children. These provisions can be applied to punish parents who engage in corporal punishment, provided the severity of the punishment meets specific criteria. This subsection summarizes current legal provisions protecting children from violence in the Czech Republic.

The Czech Charter of Fundamental Rights and Freedoms does not explicitly protect children against violence. However, Article 7(2) states that no one shall be subjected to torture or cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment or punishment, a provision that also applies to children.

Article 32(1) of the Charter guarantees the protection of the family and children, including special protection for children and young people. However, it does not specify the manner and extent of this protection. Pavel Molek, a legal scholar and a Supreme Administrative Court judge, notes that this is considered a social right rather than a fundamental right. The Constitutional Court confirms this classification, emphasizing that it should be interpreted accordingly.18x Pavel Molek, Fundamental Rights – Dignity, Prague: Wolters Kluwer 2017, p. 424.

Under Article 32(4), parents have the right to care for and educate their children, and children the right to be cared for and educated by their parents. This implies that state power should not interfere with family care, but must also provide special protection for parental care, recognizing it as a right for both the child and the parent. Special protection for children stems from their inherent vulnerability. Kateřina Šimáčková, a judge at the European Court of Human Rights, asserts that children require unique guarantees, care, and appropriate legal protection due to their physical and mental immaturity, both before and after birth.19x Kateřina Šimáčková, ‘Article 32 – Protection of Parenthood, Family, Children and Adolescents’, in: Ivo Pospíšil et al., Charter of Fundamental Rights and Freedoms. Commentary – 2nd edition, Prague: Wolters Kluwer 2023.

Article 10 of the Charter protects family life, ensuring the right to private and family life as per Article 10(2) of the Charter and Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights. These provisions prevent public authorities from arbitrarily interfering with individuals’ intimate spheres, such as relationships between parents and children. These relationships are essential to human identity and must be respected by the law.Criminal Law Provisions Against Child Abuse

Article 198 of the Penal Code defines the offence of mistreatment of a dependent person, punishable by imprisonment for one to five years, with up to twelve years if the victim dies. The Supreme Court of the Czech Republic defines cruelty as follows: ‘Abuse is the ill-treatment of another person which is characterised above all by a higher degree of rudeness and callousness, as well as a certain degree of permanence, and at the same time reaches such an intensity that it is capable of producing a state of affairs in which the person subjected to such treatment feels it as a severe disadvantage.’20x Resolution of the Supreme Court of the Czech Republic, 19.12.2017, sp. zn. 6 Tdo 1512/2017. Ill-treatment is characterised in particular by a higher degree of harshness and callousness, as well as by a certain degree of permanence, and at the same time reaches such intensity that it is capable of producing a state where the person subjected to such treatment feels it as a severe disadvantage. It is not necessary in a particular case that the person who has been ill-treated should suffer any consequences in the form of injury or other similar harm, since the ill-treatment need not necessarily be of a physical nature.21x Decision of the Supreme Court of the Czech Republic, 19.12.2017, sp. zn. 6 Tdo 1512/2017. Examples include systematic brutal beatings, kicking, painful hair-pulling, prolonged kneeling with arms outstretched, tying the child to a table or radiator, leaving the child in a cold environment without necessary clothing, forcing heavy labour disproportionate to the child’s age and physical condition, denying sufficient food, and frequent night awakenings.22x Bulletin of the Supreme Court, č. 2/1983-3. To make this provision applicable, the child must be subjected to prolonged abuse; ‘ordinary’ corporal punishment does not meet the criteria for this criminal offense.

In the context of criminal law, the perpetrator of corporal punishment, typically a parent, may commit other crimes. The most typical ones include ‘Grievous bodily harm’ (section 145) or ‘Abuse of a person living in a common dwelling’ (section 199).

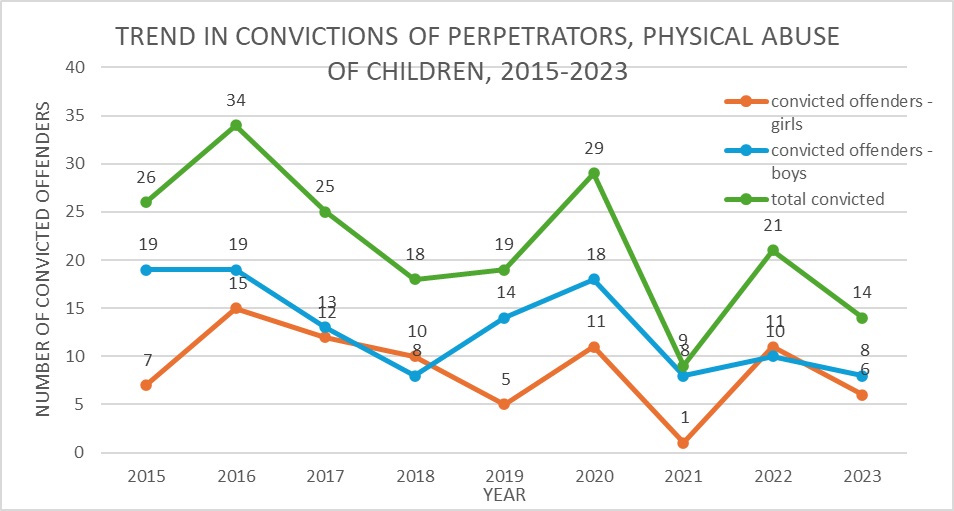

According to summary statistics from the Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs, between 2015 and 2023 on average 21 offenders were convicted per year, a total of 195 people for unspecified offences in connection with the physical abuse of children.23x Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs, Statistics, 2015-2023, www.mpsv.cz/statistiky-1. Between 2016 and 2022, a total of 295 persons were sentenced for the offence of mistreatment of a dependent person, 180 of them to suspended prison sentences, another 72 to suspended prison sentences with supervision, two offenders were sentenced to community service and only 41 offenders (i.e. 14%) were sentenced to unconditional prison sentences.24x How do we punish? https://jaktrestame.cz/aplikace/#appka_here.Administrative Measures for Child protection

The Act on Social and Legal Protection of Children focuses on safeguarding the child’s right to a favourable development and proper upbringing, protecting the child’s legitimate interests including their property, and helping repair any disrupted family functions. This Act plays a crucial role in ensuring comprehensive child protection in the Czech Republic.

Under Section 59(1)(h) of the Act on Social and Legal Protection of Children, corporal punishment of children is punishable. This provision stipulates that an offence is committed by using an inappropriate educational measure or restriction against a child, subject to a fine of up to CZK 50,000, which equals € 2,000. However, the term ‘inappropriate educational measure’ lacks precise definition due to the absence of comprehensive case law, leaving its interpretation somewhat ambiguous. Opinions differ in the academic literature regarding corporal punishment. Some scholars consider it to be a disproportionate means of discipline,25x Miloslav Macela, Act on Social and Legal Protection of Children: commentary. 2. ed. Prague: Wolters Kluwer 2019, p. 761. while others argue that ‘spanking is probably not considered a disproportionate means of discipline’ due to the prevailing societal tolerance of corporal punishment in Czech society.26x Romana Rogalewiczová, ‘Offences related to childcare’, in: Romana Rogalewiczová, Kateřina Cilečková, Zdeněk Kapitán, Martin Doležal, et al. Act on Social and Legal Protection of Children. 1. ed. Prague: C.H. Beck 2018, p. 652.

Based on the Act on Social and Legal Protection of Children, local municipalities are responsible for enforcing this provision and ensuring the well-being of children in need. They handle cases reported to child protection services, which can be initiated by anyone who suspects a child is being mistreated. -

4. Proposed Legislation of 2023

Based on the international human rights bodies’ critique, the Ministry of Justice proposed a bill to the Czech government in 2023, explicitly prohibiting corporal punishment of children. This proposal intends to amend the current provisions of the Civil Code to align with international standards on children’s rights. This section critically examines the proposed provisions. The Chamber of Deputies has approved proposed changes in the first reading of the bill in June 2024.27x Chamber of Deputies of the Czech Republic, parliamentary press 728/0, www.psp.cz/sqw/text/orig2.sqw?idd=243039.

Section 858 of the Civil Code regulates parental responsibility, while Section 884, paragraph 2 outlines the permissible educational measures for child rearing.

Proposed Amendment to Section 858: ‘Parental responsibility includes the duties and rights of parents, which consist of caring for the child, including in particular care for their health, physical, emotional, intellectual, and moral development without corporal punishment, mental suffering, and other degrading measures; protecting the child; maintaining personal contact with the child; ensuring their upbringing and education; determining their place of residence; representing them and managing their property. This responsibility arises at the child’s birth and ends when the child acquires full legal capacity. Only a court can change the duration and scope of parental responsibility.’

Proposed Amendment to Section 884, Paragraph 2: ‘Disciplinary measures may only be used in a manner and to an extent appropriate to the circumstances, not endangering the child’s health or development, and respecting the child’s human dignity. Corporal punishment, causing mental suffering, and other degrading measures are considered to infringe on the child’s human dignity.’28x The changes are marked in bold font.

The explanatory report accompanying the proposed bill underscores the necessity of explicitly prohibiting corporal punishment, even if such a declaration does not constitute a sanctioned legal norm. The report argues that while parents should play a decisive role in raising their children, explicitly articulating the desired state of non-violent child-rearing is crucial.

The proposal aims to address this issue through a declaratory adjustment within the Civil Code, refraining from introducing new penalties for parents who occasionally resort to physical correction. Instead, it advocates for accompanying the legal adjustment with non-legislative measures, including awareness campaigns, positive parenting initiatives, and accessible support services for parents and children.

The proposed changes reflect current international trends and children’s rights protection recommendations. They aim to enhance the protection of children from corporal punishment, mental suffering, and other degrading measures, ultimately aligning Czech law with international standards. Furthermore, the proposed text is consistent with the legal frameworks of other European countries.Critical Evaluation of the Proposed Amendments

Despite aligning with international standards, the proposed legal regulation appears overly complex. In the first instance, Section 858 integrates the prohibition of corporal punishment into a broader list of parental responsibilities. This integration may obscure the specific prohibition for less attentive readers, as the phrase ‘without corporal punishment, mental suffering, and other degrading measures’ is embedded within a longer sentence focused on positive duties.

The second provision presumes that corporal punishment and similar measures infringe on a child’s human dignity. This construction is somewhat convoluted, requiring the reader to infer the prohibition from two separate statements. A more precise, direct articulation that explicitly states the prohibition would enhance comprehension and enforcement.

The proposed amendments to the Czech Civil Code represent a significant step towards enhancing the legal protection of children from corporal punishment and other forms of abuse. By explicitly prohibiting such practices, the legislation aims to promote non-violent forms of child-rearing. However, to ensure effective implementation, the proposed text should be simplified to make the prohibitions clearer and more accessible. Furthermore, accompanying non-legislative measures and better law enforcement of the current legislative measures will be crucial in changing societal attitudes towards corporal punishment and supporting parents in adopting positive disciplinary practices. -

5. Trends in Reported Cases of Child Abuse

Although the current legal framework in the Czech Republic appears to offer sufficient protection for children, it falls short of international standards as it does not explicitly prohibit all forms of corporal punishment. The primary issue lies in the inconsistent enforcement of these laws. This section presents data collected by Czech ministries and the research findings to illustrate these trends.

Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs’ statistics indicate that between 2015 and 2023, an average of 21 perpetrators per year, totalling 195 individuals, were convicted for various offences related to child physical abuse.Trends in convictions of perpetrators, physical abuse of children, 2015-2023. Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs: www.mpsv.cz/statistiky-1

From 2016 to 2022, 295 individuals were sentenced for mistreating a dependent person. Of these, 180 received suspended prison sentences, 72 were given suspended sentences with supervision, two were sentenced to community service, and only 41 (14%) received unconditional prison sentences. This number of sentences highlights a trend towards lenient sentencing.

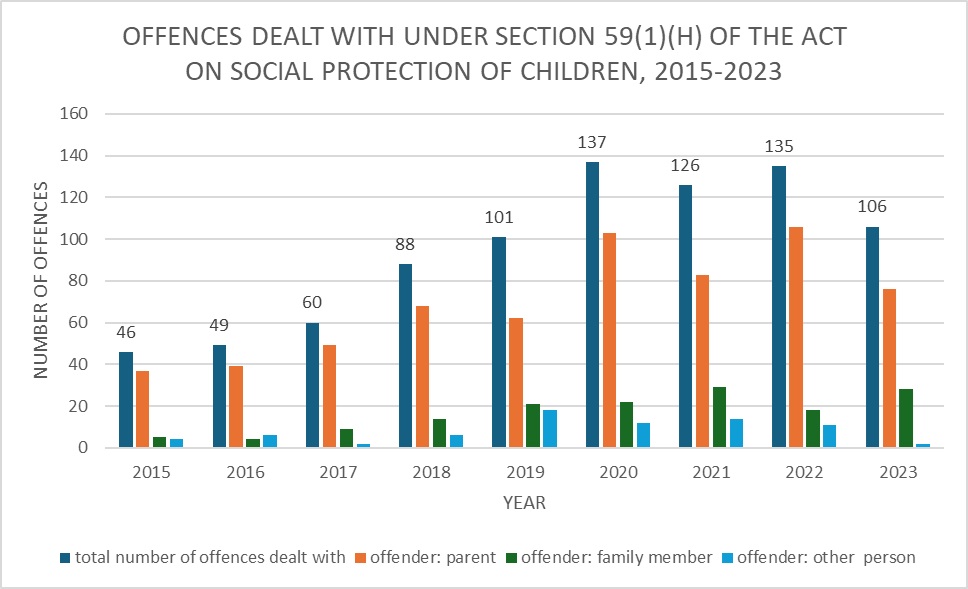

Between 2015 and 2023, the Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs handled 848 cases of offence Under Section 59(1)(h) of the Act on Social and Legal Protection of Children. The number of cases increased significantly, from 46-88 per year between 2015 and 2018 to an average of 121 per year from 2019 to 2023. This upward trend indicates growing attention to these offences.

In 2015, 46 individuals (including 37 parents) were prosecuted for offences, compared to 106 individuals (including 76 parents) in 2023. This reflects a significant increase in prosecutions for inappropriate educational measures until 2022, though there was a return to 2019 levels in 2023.Offences dealt with under section 59(1)(h) of the Act on social protection of children. Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs: www.mpsv.cz/statistiky-1

Methodology

This empirical study uses quantitative approach to find out whether the law is enforced effectively, and that children at risk of corporal punishment are protected in their families. During conducting the research in July 2024, I sent two questions to local child protection services in Czech municipalities. The questions I asked are these:

How many offences under Section 59(1)(h) of Act No.359/1999 Coll., on the Social and Legal Protection of Children, have been dealt with by your office from 2017 to the end of June 2024 in each year?

In what way were the offences decided?

The hypotheses are that if the Czech law prohibits corporal punishment and establishes an offence, enforcement mechanisms should be visible at the municipal level.

The research surveyed 32 municipalities with extended jurisdiction (hereinafter ‘municipalities’), representing about one-quarter of the Czech population, to gather data on offences under the Act on Social and Legal Protection of Children handled between January 2017 and June 2024. I contacted all regional cities, two selected municipalities of Prague and Brno, and one of the larger municipalities from each region. The other municipalities were selected randomly. The focus was primarily on bigger cities with more inhabitants and robust municipal offices. When using the number of inhabitants, the population is used from the dataset of Czech Statistical Office as of 1 January 2024.29x Czech Statistical Office, Number of inhabitants in administrative districts of municipalities with extended jurisdiction of the Czech Republic as of 1 January 2024: https://csu.gov.cz/produkty/pocet-obyvatel-v-obcich-9vln2prayv.Incidence Rates by Municipality

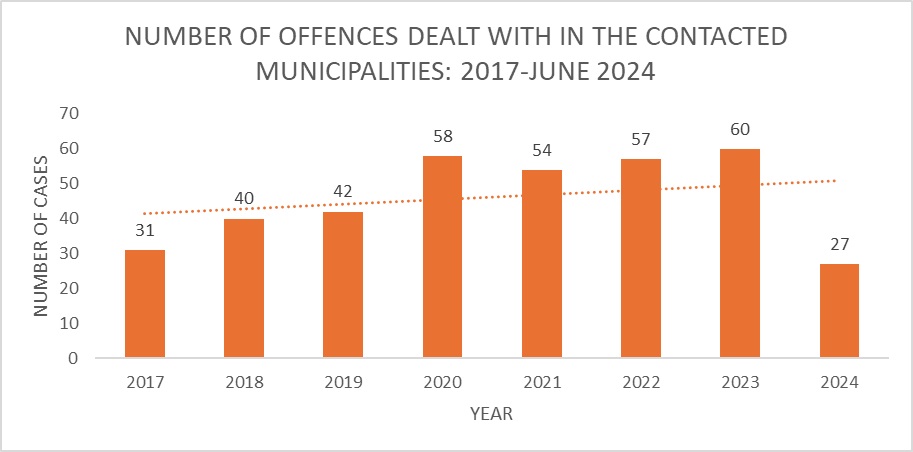

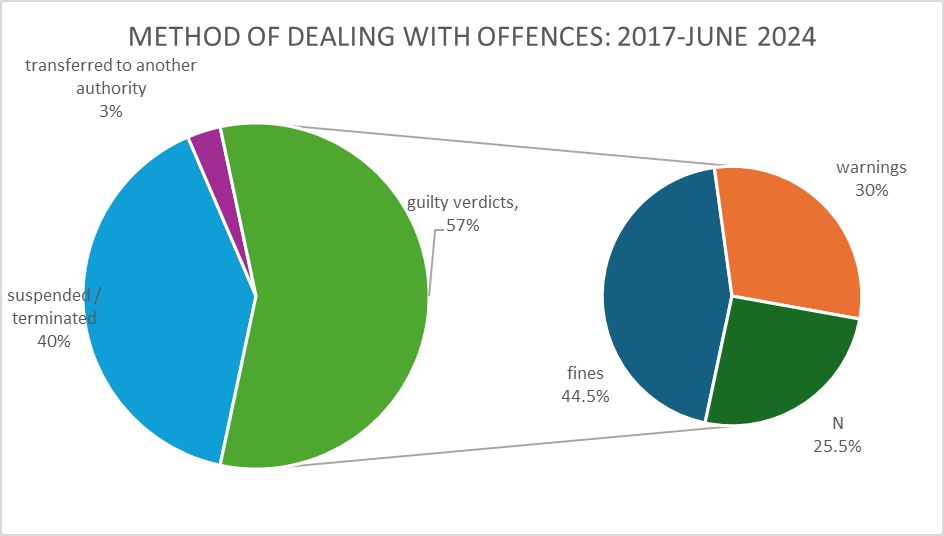

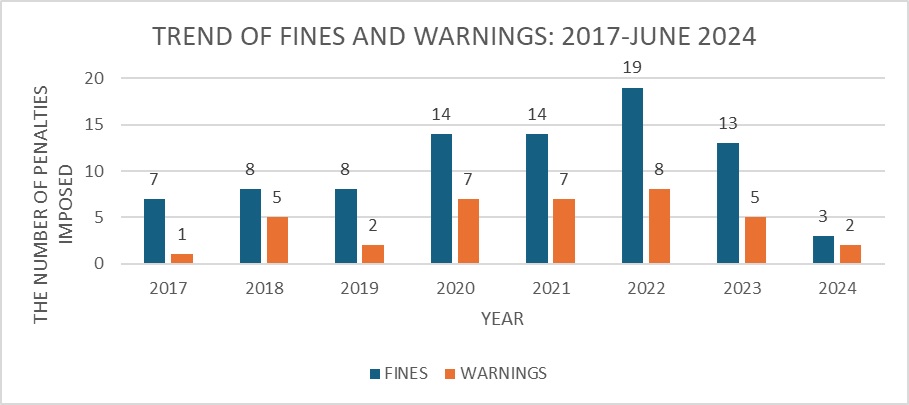

In total, 369 offences were dealt with in these municipalities between 2017 and the first half of 2024. More than half of the offenders are deemed guilty: 44.5% of offenders are fined an average of CZK 2,240 (approximately € 88), and 30% of offenders are reprimanded with warnings. Other municipalities do not state how the offenders were punished. A fairly upward trend in the imposition of fines and warnings can be observed, however the data from each year do not provide enough evidence for societal norms changing or effectiveness of the reporting procedure. In addition to that, the number of cases is too small to draw any conclusions.

Number of offences dealt with in the contacted municipalities: 2017-June 2024

In 57% of cases the offenders were deemed guilty, out of those cases 89 (44.5%) were fined and 60 (30%) warnings were issued. The majority of other cases were either suspended or terminated. Some municipalities only stated that the offender was found guilty and did not specify the punishment given.30x The cases are marked ‘N’.

Method of dealing with offences: 2017-June 2024

A slight upward trend can be observed in the imposition of fines and warnings. Some municipalities indicated the amount of the fine, which on average amounts to € 88. The highest listed fine was € 395 and the lowest € 12.

Trend of fines and warnings: 2017-June 2024

The chart below shows that as the trend in the number of offences dealt with increases, the number of suspended or terminated cases also increases. It is not clear for what specific reasons notifications are suspended or terminated, such as whether some conduct is reported in order to harm the alleged offender. One of the main reasons for suspending and terminating cases might be the lack of evidence. The majority of offences happens at home and there are typically lacking any means to prove that an offence has happened in cases in which the child does not have any physical signs of injury. However, some municipalities have suspended all or a majority of the offences reported to them:

Figure 6 Number of cases discussed, suspended or terminated, by municipality in 2017-June 2024Municipality Number of cases discussed

2017–June 2024Number of suspended or terminated cases

2017–June 2024Ratio of discussed and suspended or terminated cases

2017–June 2024Bruntál 1 1 100% Ostrava 1 1 100% Praha – MČ 13

(district of the capital city)5 5 100% Sokolov 2 2 100% Svitavy 1 1 100% Nový Jičín 21 17 81% Zlín 5 4 80% Znojmo 13 10 77% Liberec 30 15 50% Pelhřimov 2 1 50% Praha – MČ 3

(district of the capital city)4 2 50% Uherské Hradiště 4 2 50% Ústí nad Labem 4 2 50% Nový Jičín and Znojmo are among the municipalities that have dealt with a relatively large number of cases, but have suspended or terminated the majority of them. A large number of cases were also suspended by other cities, such as Olomouc (20 out of 41 cases), Kladno (17 out of 37 cases), and Plzeň (9 out of 22 cases).

Several municipalities, including Benešov, Karlovy Vary, Klatovy, Říčany, Tábor, reported no offences between 2017 and mid-2024, while others like Bruntál, Brno-Královo Pole, Ostrava, Pelhřimov, Sokolov, Svitavy reported only one or two. These discrepancies suggest varying levels of enforcement and attention to child protection issues across regions.

By calculating the incidence rate per 10,000 inhabitants, we can identify the municipalities where the issue of corporal punishment of children is most frequently addressed and enforced. Among the municipalities surveyed, Česká Lípa most frequently punished residents for offences under Section 59(1)(h) of the Act on Social and Legal Protection of Children (38 offences and 27 punishments). Similar trends were observed in Olomouc and Chomutov. In contrast, the smaller municipality of Nový Jičín, with a population of 48,000, recorded only 4 punishments for 21 offences. These figures highlight the frequency of reported cases and raise questions about the underlying factors influencing these trends. It does not seem to depend on the region of the Czech Republic or the size of the office dealing with the offences. The willingness to deal with cases seems to depend on the management of the child welfare agency and the number of staff. Some municipalities only stated that the offender was found guilty and did not specify the punishment given.31x These cases are marked ‘N’.Figure 7 Number of cases between 2017-June 2024Municipality Number of cases between 2017-June 2024 Fines Warnings Convicted Number of cases per 10 thousand inhabitants Česká Lípa 38 16 11 27 4,92 Nový Jičín 21 4 N 4 4,3 Trutnov 22 14 0 14 3,51 Chomutov 24 N N 16 2,97 Kladno 37 N N 18 2,89 Olomouc 41 8 11 19 2,43 Šumperk 16 10 1 11 2,36 Conclusions: Czech Children are not Protected from Corporal Punishment in Home Settings

The analysis of municipal responses to corporal punishment cases reveals significant inconsistencies in how child protection laws are applied across different regions. The discrepancies in reporting and prosecution rates among municipalities suggest that local authorities have varying approaches to handling cases of child abuse. Firstly, the disparate handling of cases across municipalities underscores a lack of uniformity in enforcing child protection laws. While some municipalities, such as Česká Lípa, demonstrate a proactive approach to addressing and prosecuting cases, others, like Nový Jičín, exhibit less consistent enforcement. In fact, the data suggest that children in municipalities with a higher incidence of prosecution are not subjected to corporal punishment more frequently. Instead, the research indicates that local child social protection authorities in these areas are more proactive in addressing and preventing excessive punishment. Conversely, municipalities that reported few or no delinquency proceedings over the past decade are likely not addressing the issue adequately, or they may be addressing it through other means.

The observed variations also highlight the need for standardized reporting and data collection practices. Consistent and comprehensive data collection across municipalities would provide a clearer understanding of the prevalence of corporal punishment and the effectiveness of interventions. Such standardization would also facilitate the identification of best practices and areas in need of improvement.

Further research should investigate several critical areas to better understand variations in the prosecution of cases involving corporal punishment. Specifically, future studies could examine the funding mechanisms of child welfare offices, the correlation between the number of officers and the number of prosecuted cases, and the perspectives of officers through interviews on their understanding of child abuse issues. Such comprehensive research would provide insights into why some municipalities exhibit higher rates of prosecuting cases of corporal punishment against children.

Despite existing legislation, Czech children are not sufficiently protected from corporal punishment. The level of protection varies significantly depending on the actions of individual officials and the local social and legal child protection authorities. One of the main challenges identified is the inconsistent enforcement of existing laws, which depends heavily on the individual actions of child services officials. This inconsistency results in varying levels of child protection across municipalities, which suggests that some municipalities might be inadequately addressing issues related to child abuse. The most serious and visible cases of child abuse, such as those involving physical injuries requiring medical treatment, are more likely to be prosecuted. To enhance child protection, it is crucial to implement more explicit legal definitions and promote greater awareness and education about corporal punishment’s harms among the public and officials. Campaigns promoting awareness could also plainly explain the reporting procedure. Ensuring more enforcement that is consistent across municipalities could be done by implementing centralised guidelines and training for local authorities. -

6. Conclusion and Recommendations

The analysis of corporal punishment in the Czech Republic underscores the complex interplay between legal frameworks, societal attitudes, and the enforcement of child protection measures. The proposed amendments to the Civil Code in 2023 mark a significant step toward aligning Czech legislation with international standards on children’s rights. However, these changes alone are not enough to reduce the prevalence or societal acceptance of corporal punishment.

Historically, despite repeated calls from international bodies such as the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child and the European Committee of Social Rights, significant legislative gaps remain. These gaps highlight the need for more explicit legal prohibitions and comprehensive child protection measures. While offering indirect protections, the current legal framework lacks the clarity and enforcement consistency required to effectively safeguard all children.

Amendments to Civil Code Sections 858 and 884 aim to ban corporal punishment explicitly. However, the complexity of these provisions may obscure their intent and effectiveness. Simplifying the legal text to make the prohibitions more explicit and comprehensible can be essential for effective implementation and enforcement.

The analysis of reported child abuse cases highlights significant inconsistencies in enforcement across municipalities. These variations indicate that the protection children receive often depends on the actions of individual officials and local authorities. Passing a law to ban corporal punishment is only a first step; it will not be enough to change deeply ingrained societal attitudes. Promoting awareness and education about positive child rearing and training the local authorities is needed to protect children in real life.

The main research question was whether the Czech children are protected from corporal punishment in their homes, and if the current legal framework and its enforcement align with the Czech Republic’s claims that corporal punishment is already prohibited in all settings. Credible estimates suggest that between 280,000 and 367,000 children are at risk in the Czech Republic. Given that annually there are only up to 137 cases prosecuted under section 59(1)(h) of the Act on Social Protection of Children, I conclude that from this research it is uncovered that current protection of children is not sufficient to protect all children who are subjected to corporal punishment or at risk of it in their families. The enforcement level of the Act on Social Protection of Children varies across the Czech Republic, depending on the individual municipality. Last but not least, the Czech Republic’s claim is not true: the corporal punishment is not banned in all settings. This conclusion is supported by the international human rights committees, such as the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child, and the European Committee of Social Rights ruling and legislation proposed in 2023. -

1 Radek Dragoun & Barbora Doubravová, ‘Slapping a child can set boundaries, I don’t want to forbid it to parents, says Jurečka’, 27.1.2022.

-

2 Charles University, 1st Faculty of Medicine, ‘Physical punishment is demonstrably harmful to children. How much do Czechs use them?’, 27.6.2023. Widespread support for corporal punishment is declining only very slowly, with 63% of parents surveyed in 2018 reporting that they had used corporal punishment in parenting at least once. Open Men’s League, Physical punishments, 2018.

-

3 Klára Španělová, ‘Abused Children Interrogated by 47 People. Domestic violence often goes unreported, experts say’, Aktuálně.cz.

-

4 Miloš Velemínský and others, ‘Prevalence of Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) in the Czech Republic’ (2020) 102 Child Abuse & Neglect 104249.

-

5 The SOFA authors based their findings on research data from ibid. ACE stands for Adverse Childhood Experience, www.societyforall.cz/prestanme-prehlizet-ohrozeni-deti.

-

6 Civil Code, Law No. 89/2012 Coll.

-

7 Criminal Code, Law No. 40/2009 Coll.

-

8 UN CRC, General comment no. 8: The Right of the Child to Protection from Corporal Punishment and Other Cruel or Degrading Forms of Punishment 2006, CRC/C/GC/8., para. 11.

-

9 CRC Concluding observations on Czech Republic, 1997, CRC/C/15/Add.81, para. 18 and 35.

-

10 CRC Concluding observations on Czech Republic, 2003, CRC/C/15/Add.201, para. 40 and 41.

-

11 Family Act, Law No. 94/1963 Coll. The law was repealed as of January 1, 2014.

-

12 The Act on Social and Legal Protection of Children, Law No. 359/1999 Coll., section 59(1)(h) of the Act

-

13 The Third and Fourth Periodic Report on Fulfilment of the Obligations arising from The Convention on the Rights of the Child. 2008. https://vlada.gov.cz/assets/ppov/rlp/dokumenty/zpravy-plneni-mezin-umluv/The_Third_and_Fourth_Periodic_Report.pdf, para. 133-135.

-

14 CRC, Concluding observations, 2011, CRC/C/CZE/CO/3-4, para. 39-42.

-

15 UN CRC, Concluding observations on Czechia, CRC/C/CZE/CO/5-6, 2021, para. 24. UN Human Rights Council, 2012, A/HRC/22/3, para. 94.88-94.90. UN CAT, Concluding observations, 2012, CAT/C/CZE/CO/4-5, para. 22.

-

16 Statement of the Government of the Czech Republic on the collective complaint filed against the Czech Republic for violation of the European Social Charter due to the absence of legislation explicitly prohibiting corporal punishment of children in the family, at school and other institutions and places, www.mpsv.cz/documents/20142/1037493/vi_2014_27_p1.pdf/9b9f3a82-d44d-314a-a9c3-634b5fae0b97.

-

17 Decision on the merits: Association for the Protection of all Children (APPROACH) Ltd v. Czech Republic, Complaint No. 96/2013.

-

18 Pavel Molek, Fundamental Rights – Dignity, Prague: Wolters Kluwer 2017, p. 424.

-

19 Kateřina Šimáčková, ‘Article 32 – Protection of Parenthood, Family, Children and Adolescents’, in: Ivo Pospíšil et al., Charter of Fundamental Rights and Freedoms. Commentary – 2nd edition, Prague: Wolters Kluwer 2023.

-

20 Resolution of the Supreme Court of the Czech Republic, 19.12.2017, sp. zn. 6 Tdo 1512/2017.

-

21 Decision of the Supreme Court of the Czech Republic, 19.12.2017, sp. zn. 6 Tdo 1512/2017.

-

22 Bulletin of the Supreme Court, č. 2/1983-3.

-

23 Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs, Statistics, 2015-2023, www.mpsv.cz/statistiky-1.

-

24 How do we punish? https://jaktrestame.cz/aplikace/#appka_here.

-

25 Miloslav Macela, Act on Social and Legal Protection of Children: commentary. 2. ed. Prague: Wolters Kluwer 2019, p. 761.

-

26 Romana Rogalewiczová, ‘Offences related to childcare’, in: Romana Rogalewiczová, Kateřina Cilečková, Zdeněk Kapitán, Martin Doležal, et al. Act on Social and Legal Protection of Children. 1. ed. Prague: C.H. Beck 2018, p. 652.

-

27 Chamber of Deputies of the Czech Republic, parliamentary press 728/0, www.psp.cz/sqw/text/orig2.sqw?idd=243039.

-

28 The changes are marked in bold font.

-

29 Czech Statistical Office, Number of inhabitants in administrative districts of municipalities with extended jurisdiction of the Czech Republic as of 1 January 2024: https://csu.gov.cz/produkty/pocet-obyvatel-v-obcich-9vln2prayv.

-

30 The cases are marked ‘N’.

-

31 These cases are marked ‘N’.

Citeerwijze van dit artikel:

Zuzana Vanyskova, ‘The Legal Framework for Child Protection from Corporal Punishment in the Czech Republic’, Family & Law 2025, januari-maart, DOI: 10.5553/FenR/.000068

Family & Law |

|

| Artikel | The Legal Framework for Child Protection from Corporal Punishment in the Czech Republic |

| Keywords | Child welfare, Corporal punishment, Children, Law enforcement, Czech Republic |

| Authors | Zuzana Vanyskova |

| DOI | 10.5553/FenR/.000068 |

|

Show PDF Show fullscreen Abstract Author's information Statistics Citation |

| This article has been viewed times. |

| This article been downloaded 0 times. |

Zuzana Vanyskova, 'The Legal Framework for Child Protection from Corporal Punishment in the Czech Republic', Family & Law February 2025, DOI: 10.5553/FenR/.000068

|

This article addresses the persistent issue of corporal punishment of children in the Czech Republic. Despite statistics indicating that 58% of parents have used corporal punishment, the country has yet to implement an explicit ban on such practices in family settings. This reluctance persists despite two decades of international pressure from organizations like the United Nations and the European Committee of Social Rights. The article examines the historical and legislative background, highlighting key international recommendations and local legal responses including a detailed analysis of existing legal provisions that indirectly protect children, such as the Czech Charter of Fundamental Rights and Freedoms and various criminal and administrative laws. The article discusses the legislation proposed in 2023, which aims to explicitly ban corporal punishment through amendments to the Civil Code. The proposed amendments outline parental responsibilities, stating that parents must care for their children without corporal punishment, mental suffering, or degrading measures. The article critically evaluates these proposals, emphasizing the need for simpler legal language. The article also employs quantitative methods to analyse how individual municipalities enforce child protection laws, revealing significant regional disparities in prosecution rates. The findings suggest that child protection varies based on local authorities’ actions, with some municipalities demonstrating proactive approaches and others showing minimal enforcement efforts. The findings suggest that enforcement of child protection laws varies significantly by region, affecting children’s protection from corporal punishment. Additionally, the societal acceptance of corporal punishment remains deeply ingrained. The study concludes that stronger legal frameworks and public awareness efforts are essential to promote non-violent child-rearing practices in the Czech Republic. While legal reforms are crucial, they must be accompanied by educational campaigns to shift public attitudes. |